Oscar Mix-up – Lessons Learned

“Who Said What When” is at the Center of Most Disputes

01/03/2017Are you ready for GDPR?

11/04/2017When the 2017 Oscar for “Best Picture” was mistakenly awarded to “La La Land” in front of 33 million live viewers, you could practically feel the embarrassment radiating from all parties involved.

For the executives of PricewaterhouseCooper (PwC), the company in charge of tallying votes and assuring the utmost secrecy and accuracy of the results, there was a simple explanation for the fiasco.

“At the end of the day we made a human error”, Tim Ryan, U.S. Chairman and Senior Partner of PwC told USA TODAY.

Ah, yes: “To err is human; to forgive, divine.” But what is often less understood is the degree to which human error is exploited.

Cybercriminals Prey on Human Weakness

In the realm of cybercrime, “human error” is exactly what many cybercriminals are now exploiting. Never mind corporate firewalls, bulletproof IT policies, and military-grade encryption – some of the most successful cyberattacks today ignore all those things and simply go after the weakest link in the chain: the human being.

For example, in phishing attacks that have up to now caused an estimated $5 billion (USD) in damages worldwide, a cybercriminal tries to trick humans into thinking their phony emails and websites are legitimate emails and websites of trusted companies and service providers. When people fall for this trick (and they often do), they end up literally sending cybercriminals their account logins, credit card info, and even social security numbers, exposing themselves to significant financial harm. Although the phony emails and websites may look genuine at a glance, there are telltale ways to know they’re fake, often even before you click a single link.

One Person’s Mistake Could Bankrupt a Company

As with phishing, cybercriminals are now using the same principle of targeting human weakness in the business world with one of the most successful Internet scams in recent years.

Business Email Compromise (BEC), as the FBI calls it, describes an attack whereby a cybercriminal uses “imposter emails” to lure fund transfers or the transfer of valuable business information from corporate finance, HR, or other unsuspecting employees.

In a BEC attack, cybercriminals use simple techniques to learn about a company’s organisational structure. They can easily search for a company via LinkedIn’s website and identify key executives and finance staff, including the CEO, finance director, and accounting managers. From there, it’s simply a matter of social engineering. The cybercriminal writes an “imposter email” that appears to be from the CEO or other top management personnel, instructing an unsuspecting accounting manager to send an urgent wire transfer. The manager complies, not noticing anything unusual in the manner of request or in the imposter email. By the time the manager discovers the error, the money has already been wired to the criminal’s overseas account and can no longer be recovered.

There is no hacking involved in BEC; instead, the victim willingly provides confidential business information or a cash transfer, under false pretenses. Because there is no technical breach, cyber insurance policies don’t cover the loss.

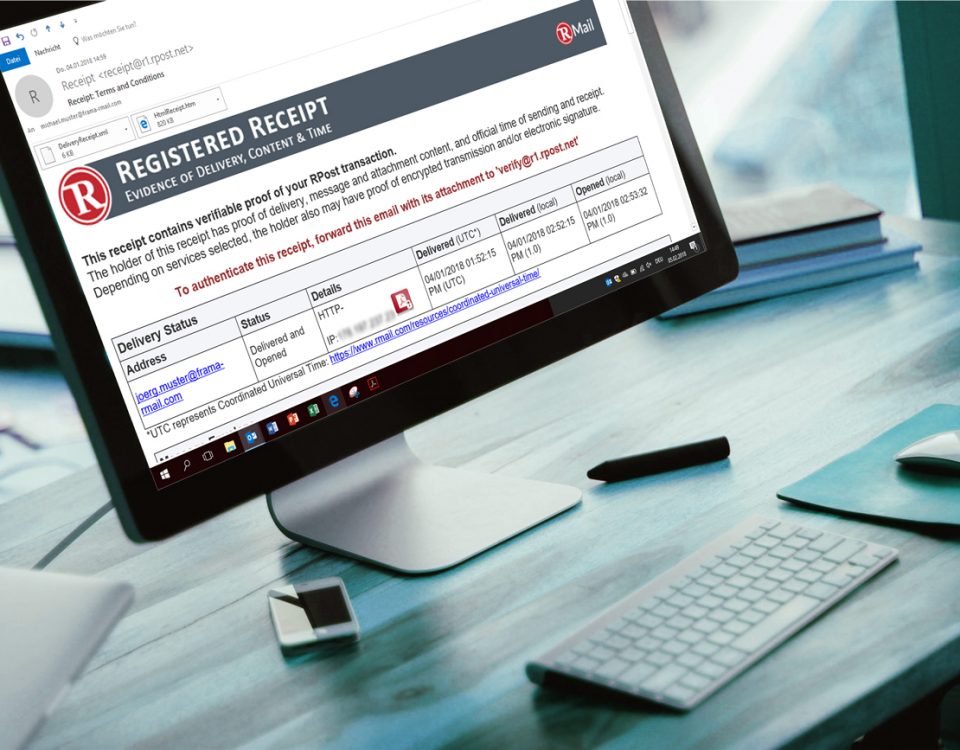

RMail’s “anti-whaling” security feature uses proprietary algorithms to analyse email message characteristics, flagging a message when it appears to be an “imposter email,” such as those used in BEC attacks. RMail’s anti-whaling feature is available to RMail users in the most recent version of the RMail add-in for Microsoft Outlook.

This article was written in collaboration with RPost US Inc. Los Angeles, author: Arielle Castro